Note: This should have been posted days ago. Sorry about that, but here it is!

You can read part 1 here and part 2 here.

How does a reasonably intelligent, well-educated person, interested in and accepting of science, who views themselves as rational (whether it’s true or not) and mindful, come to an experience like this one, and what do I (being the person described above) take away from it? How do I process and interpret it?

Here’s another question: how can I write about this experience and not completely destroy my credibility? If I’m being honest, I have to start by admitting that for some people’s purposes, I can’t. A true skeptic is going to want far more than my say-so, and I don’t have more than that to offer. I have my eyewitness account, which is not objective proof of anything.

I’ve spoken to Matt about it since. He remembers that day but not clearly. He remembers that I told him I saw a pixie, and that I agree with his friend that there may be fairies in those woods, but not that a damselfly followed us. As time goes on, the incident lives only in my memory, though it remains vivid.

Now, I wouldn’t say I’m a skeptic, though I wouldn’t describe myself as credulous, either. I’m willing to examine or to re-examine any idea and I don’t believe most things in this world don’t have have clear-cut “yes” or “no” answers.

Are there fairies? Probably not.

Is there other intelligent life in the universe? I’d say that there must be, almost certainly. In this century, we have discovered hundreds of exoplanets – planets beyond our solar system – in our nearby galactic neighborhood. We’ve even begun to find the little, Earth-like worlds that might bear life similar to our own, though we haven’t yet found that life.

Is Schrödinger’s cat alive or dead? Yes. My understanding of the uncertainty principle is not that the unseen cat in the box is both alive and dead, but that because we don’t know one way or the other, we have to include in predictions we make involving the cat in the box both possibilities, with the knowledge that the cat certainly is in a single state, alive or dead. Until we know one way or the other, both might be true.

Is Schrödinger’s cat undead? We have no prior example of this condition available, so the probability of a zombie cat inside Schrödinger’s box is pretty much nil.

But in my memory is a clear image of a five-inch-long, quite handsome, fierce little blue man with gossamer wings.

Maybe I’m a little bit like Percival Lowell the astronomer, in that I’m captivated by a romantic notion. Lowell took something he misunderstood and turned it into his life’s work, and swayed not only generations of young dreamers, but got the University of Arizona, among other bastions of respectability and learnedness, to support his search.

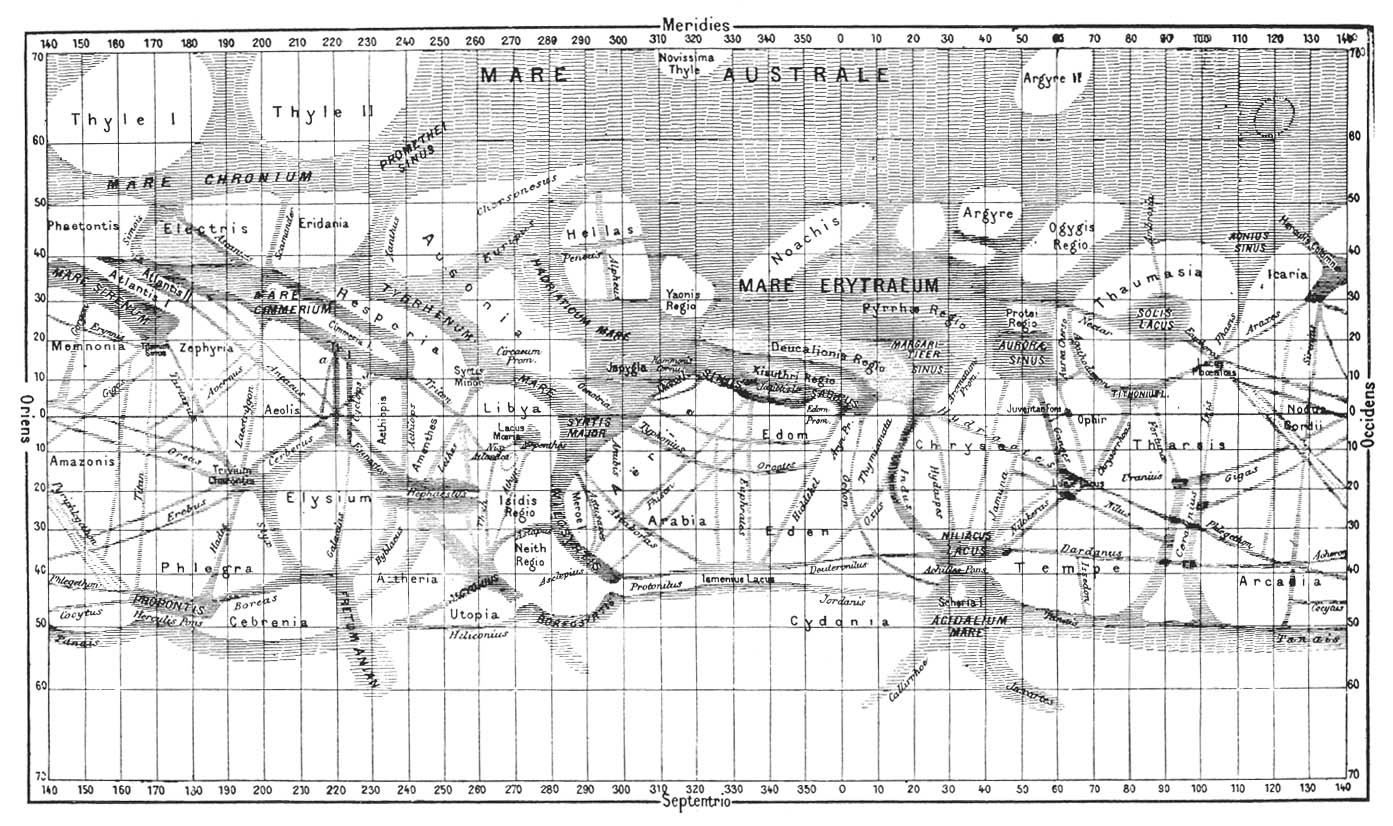

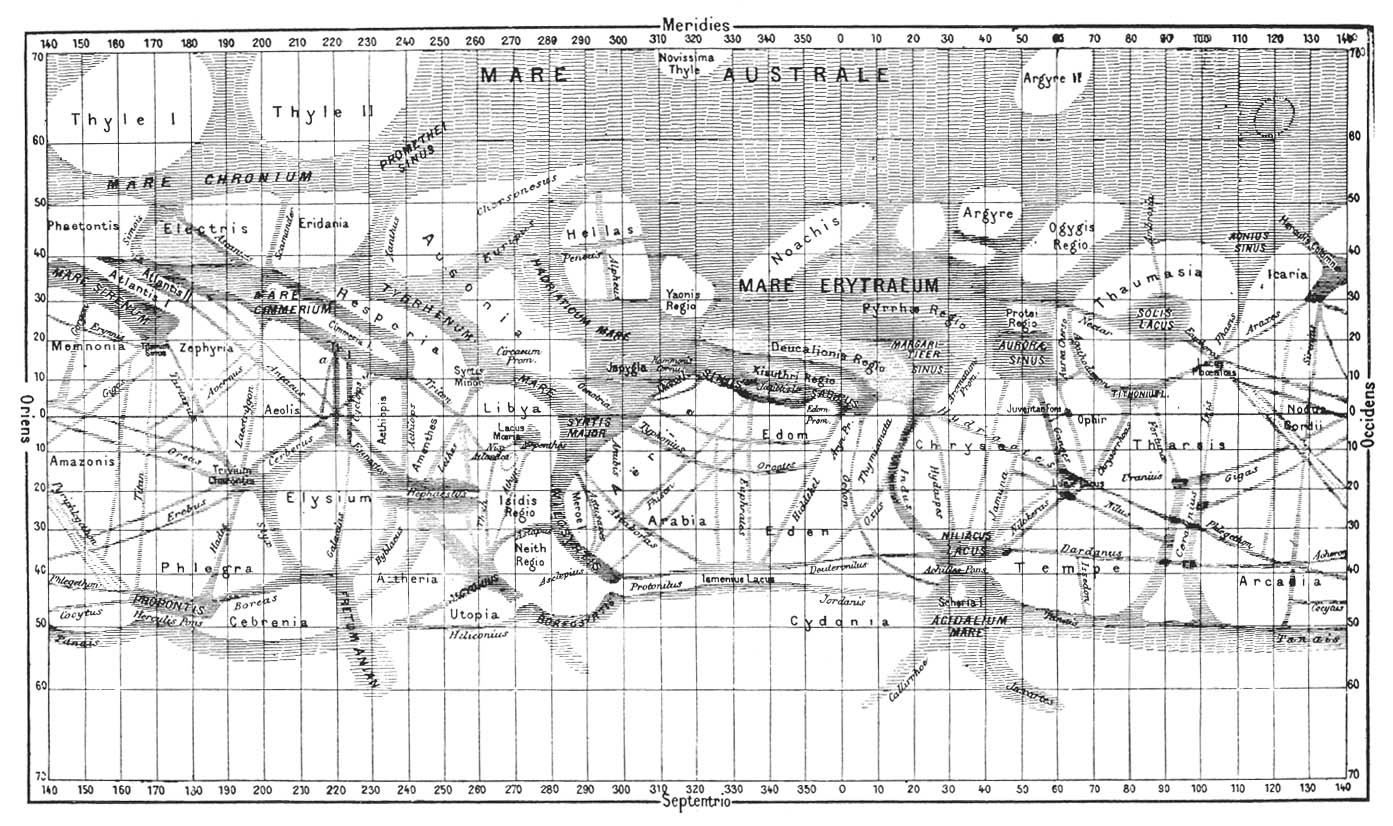

The Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, using a new, higher-powered telescope developed in the late nineteenth century, spent a great deal of time studying Mars at a closer level of detail than had previously been possible. He made a number of discoveries about the surface of the planet, including a seasonal change in the coloration of some regions of the surface, a darkening that seemed associated with the warmer temperatures of Martian summer. He discovered the immense Martian sandstorms that can cover the entire surface of the planet for weeks at a time. He also noticed some deeper channels cut into the surface of Mars that ran in straight lines for long distances. He called them “canali,” marking them on the beautiful hand-rendered maps he made of the Martian surface.

Lowell, an American planetary astronomer of some renown, saw Schiaparelli’s maps and became obsessed with the notion of the Canals of Mars, envisioning them as immense artificially-created waterways, marvelous feats of engineering created in an effort to conserve water by an ancient and advanced civilization, purposed towards saving a desertified, dying world.

Schiaparelli, learning of Lowell’s enthusiasm, wrote to him, explaining that “canali” was the Italian word for “channel,” referring to striations observed on the Martian surface without any inference of intelligent purpose intended or necessary, and furthermore that he had seen nothing to suggest that the canali were, in fact, evidence of intelligence, much less the advanced engineering marvels Lowell was busy convincing himself and others that they were.

No matter. Lowell continued to pursue his obsession, to the point of getting the Lowell Observatory at Kitt Peak in Arizona built with the intention of exploring the surface of Mars as closely as possible.

Over time, the dream of Martian canals has faded and died, though it burned brightly for a time in the popular imagination. From Lowell’s misinterpretation of Schiaparelli, we have been gifted with enduring adventure classics like H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, Edgar Rice Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars and ten more books featuring the former Civil War Captain John Carter, and the contemplative Robert A. Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, the story of a human infant, sole survivor of a failed Martian expedition who is raised by ancient and mysterious Martians, who comes back to Earth to become a prophet for the modern age. The book was controversial and influential in its time, and would not have existed but for Percival Lowell’s misreading of Giovanni Schiaparelli’s work.

Lowell was wrong, we know that for certain. In fact, it was known at the time that Lowell’s ideas were probably fanciful. But it’s also true that his fancies have left a mark on reality. If I’m like him, it’s in my willingness to entertain an idea that holds little objective merit, for reasons of my own. I’m different from him in that I don’t have any particular ambition to convince people that my fanciful ideas are real.

I actually hope what I saw never proves to be real. How disappointing it would be to have the existence of pixies, unicorns, or other such creatures confirmed by science: perhaps more disappointing than if someone were able to prove the negative, that fairies are, indeed, mere products of fertile imaginations and romantic hearts like mine.

You must be logged in to post a comment.